Resolution 60.29 of the World Health Assembly (WHA) on Health Technologies recognises that medical devices are indispensable tools in the provision of medical care for prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation. It also recognises that they are essential to achieving internationally-agreed health-related development goals, including those set by the Millennium Declaration (1).

In addition, the WHA resolution 61.21 on the global strategy and action plan on public health, innovation and intellectual property acknowledges that current initiatives are not sufficient to overcome the challenges of guaranteeing access and facilitating the innovation of health products and medical devices (2).

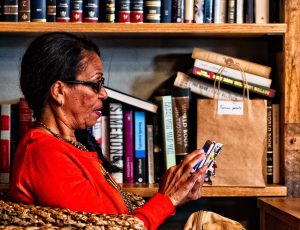

Assistive technologies enable people to live healthy, productive, independent, and dignified lives, and to participate in education, the labour market and civic life. Furthermore, these technologies help reduce the need for formal health and support services and long-term assistance, as well as ease the burden of care placed on caregivers (3).

Without assistive technology, people are often excluded, isolated, and locked into poverty, thereby increasing the impact of disease and disability (4).

With an ageing population in Europe, cognitive, neurological, cardiac disorders and other chronic illnesses are becoming more frequent, generating changes in social and health needs (5). This reality is associated with the incidence of multi-morbidities – where two or more chronic illnesses co-occur – which makes it important to re-orient health systems towards better monitoring the population and promoting greater independence (5, 6).

Improving the quality of life of patients and those around them is one of the priority objectives of the European Union (7). TeNDER adopts this priority as a guiding principle. In practice, the project tools integrate a modular, personalised system capable of recognising changes in habitual behaviour, movements and mood using a multisensory system. This information is then shared with all relevant actors involved in the patient’s care.

Who can benefit from TeNDER?

– Patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD) and co-morbidity with other chronic illnesses, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD).

– Caregivers: formal and informal ones.

– Social and health care professionals: physicians, nurses, physiotherapists, social workers, etc.

– Patient associations.

Which health, well-being and socioeconomic benefits?

TeNDER‘s integrated care approach incorporates assistive technologies, and this can have a positive impact on the health and well-being of a person and their family, as well as broader socioeconomic benefits. For example:

– The doctor and the patient will be alerted when cardiovascular risk begins to present complications in her/his health condition, having the possibility of anticipating a cardiovascular event (8).

– The caregiver of a person with dementia may know the location of the patient and whether she/he is at home, in the neighbourhood, or has gone off their usual paths, having the possibility of finding the patient in case she/he gets lost (9).

– A physiotherapist may have a record of a patient’s gait pattern to further individualise treatment (10).

– A social worker can be alerted if the home of a dementia patient does not meet the conditions for decent housing in the event of inadequate temperature, electricity problems, gas leaks, etc. (3).

These examples illustrate how assistive technologies play an essential role in TeNDER’s integrated care framework, which also takes great care to ensure the privacy of patients and to protect the data they generate to keep them safe.

References:

1. Sixtieth World Health Assembly. Health Technologies. WHA60.29. 2007; May: 2-3. Available from: http://www.who.int/medical_devices/resolution_wha60_29-en1.pdf

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy and Plan of Action. 2011.

3. Piau A, Wild K, Mattek N, Kaye J. Current state of digital biomarker technologies for real-life, home-based monitoring of cognitive function for mild cognitive impairment to mild Alzheimer disease and implications for clinical care: Systematic review. Vol. 21, Journal of Medical Internet Research. Journal of Medical Internet Research; 2019.

4. Huckvale K, Venkatesh S, Christensen H. Toward clinical digital phenotyping: a timely opportunity to consider purpose, quality, and safety. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2019 Dec; 2(1).

5. Sue T. Expert patients: Sue Thomas explains why the government’s Expert Patient initiative will enable nurses to help patients move away from a disease focus towards independence and a better quality of life. Primary Health Care. 2001; 11(9): 20-1.

6. Haslbeck J, Zanoni S, Hartung U, Klein M, Gabriel E, Eicher M, et al. Introducing the chronic disease self-management program in Switzerland and other German-speaking countries: Findings of a cross-border adaptation using a multiple-methods approach. BMC Health Service Res [Internet]. 2015; 15(1). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1251-z

7. World Health Organization (WHO) Patient safety: Global action on patient safety. 72nd World Health Assembly: provisional agenda item 125. 2019.

8. Teo JX, Davila S, Yang C, Hii AA, Pua CJ, Yap J, et al. Digital phenotyping by consumer wearables identifies sleep-associated markers of cardiovascular disease risk and biological aging. Commun Biol. 2019 Dec 1; 2(1).

9. Kourtis LC, Regele OB, Wright JM, Jones GB. Digital biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease: the mobile/wearable devices opportunity. [cited 2020 Feb 10]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-019-0084-2

10. Vaidyam, A., Halamka, J. and Torous, J. (2019). „Actionable digital phenotyping: a framework for the delivery of just-in-time and longitudinal interventions in clinical healthcare,“ mHealth. AME Pub. mHealth. 2019 Aug; 5: 25–25.