Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, life expectancy had been steadily increasing across Europe in recent decades. This was due to a variety of factors, including reductions in childhood mortality, rising living standards, advances in medicine, and improvements in healthcare delivery.

Seguir leyendoTechnology in Stroke Recovery

Throughout the world, highly advanced wearables and sensor devices are being used on a daily basis. Advancements in the field of science and technology give rise to more effective tools for disease prevention and recovery.

Seguir leyendoA comparison of telehealth in the United States and Spain

Telemedicine has shown tremendous growth around the world recently, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only spurred an increase in the number of people who utilise telehealth services.

Seguir leyendoWhat does my day look like? A dementia perspective

We dedicate this text to those who want to learn more about how this occurs, and the support mechanisms that might stall this process and mitigate the negative consequences of the tendency toward inactivity.

Seguir leyendoAs Europe goes grey, assisted living will redefine old age

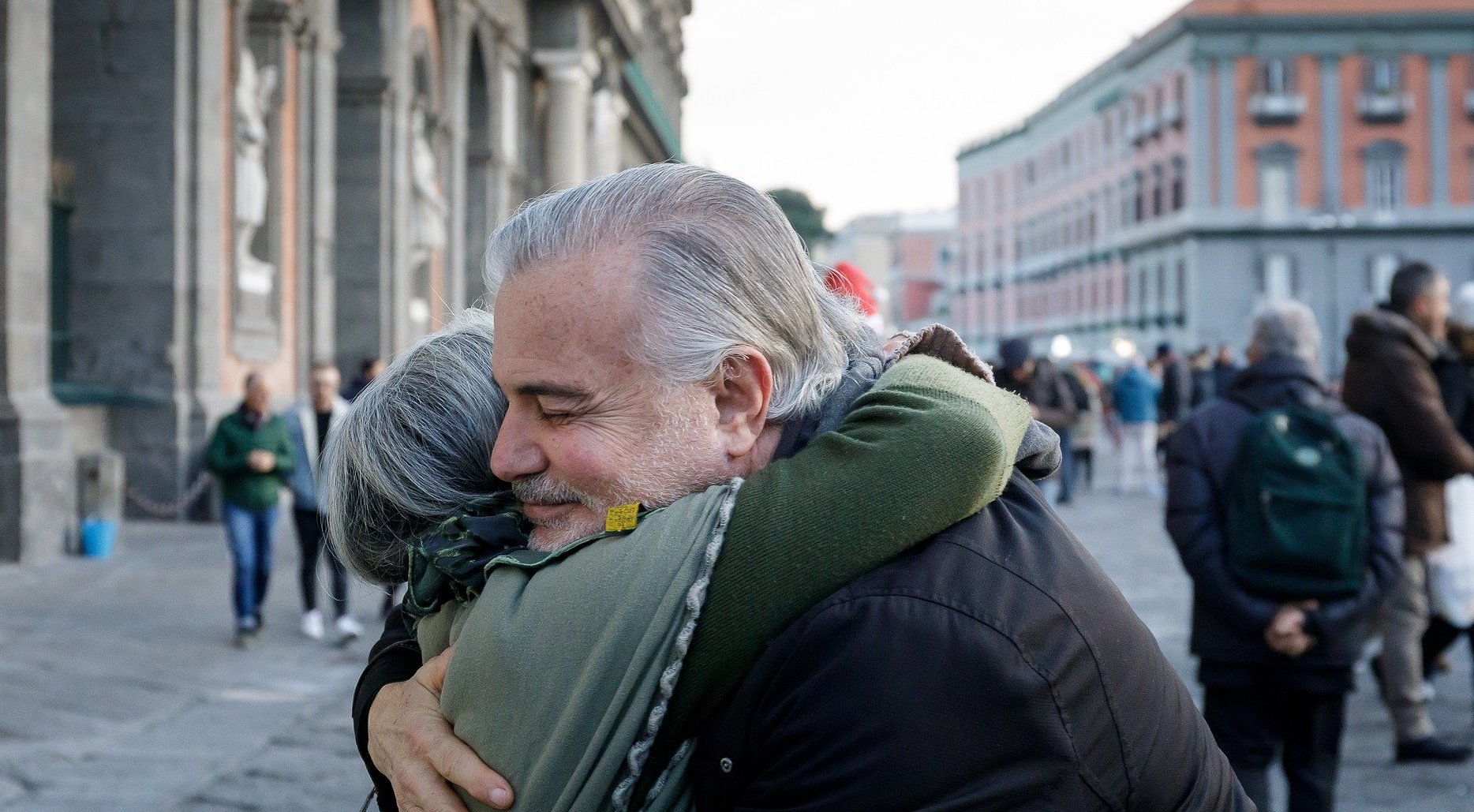

Europe is ageing. People are living longer; fertility rates are falling; and in some cases, inflows of retirees have altered countries’ demographics dramatically.

Seguir leyendoAutomatic fall detection of patients with chronic diseases using the TeNDER Health Tracking (HeTra) system

Here, we will focus on the specific ICT-based interventions designed to detect falls. The TeNDER system uses devices equipped with sensors to monitor and support the physical status of older adults.

Seguir leyendoTeNDER and the Quality of Life of people with chronic diseases

Quality of Life (QoL) is an important concept widely used in medicine, sociology, and psychology. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines QoL as an “individual’s perception of his or her position in life in the context of the culture and value system where they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’’[1].

Seguir leyendoTaking it one step further – Empowering people with technology-based systems

We’ve all been there, when feeling sick the highest aim is to get well again, preferably as soon as possible. However, this isn’t something that is within reach for everybody, especially not for people with chronic diseases, like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, or cardiovascular diseases. Due to the progressive development of such conditions, returning to a status quo is unfortunately out of reach.

Therefore, the focus needs to shift to slowing down the progression of a disease and making the best out of the situation in such a way that enables people to be as healthy as possible, and in turn, live the best life possible.

This is in accordance with the concept of Health promotion, which was defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1986 in the first conference of Health Promotion in Ottawa. Thus, health promotion is “the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health” (World Health Organization, 1986). Concrete strategies were published afterwards in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion and now serve as the foundation for the “Health for All” strategy of the WHO.

One of the basic tenets of health promotion is to enable people “to achieve their fullest health potential,” in other words, to put people in a position where they can control and can stand up for their own health. This way, people are not only passive recipients of health care, rather, they can advocate for themselves and, in a wider sense, make the best out of the situation. Having a “supportive environment, access to information, life skills and opportunities for making healthy choices,” were identified as ways to reach this goal.

Similarly, the concept of empowerment builds on the concept of enabling. According to the WHO, empowerment is “a process through which people gain greater control over decisions and actions affecting their health” (World Health Organization. Division of Health Promotion & Communication, 1998). Conditions should allow people directly to influence their health through actions – individually and as a group.

In the age of digitalisation, more and more technologies are being developed to support people in their daily lives. Ranging from simple communication tools to activity trackers or sophisticated monitoring devices, technology offers a wide spectrum of implementation possibilities. Whereby some tools are developed primarily for enjoyment, as, for example, game applications, while others offer solutions to problems in daily living and aim to increase individual control over actions.

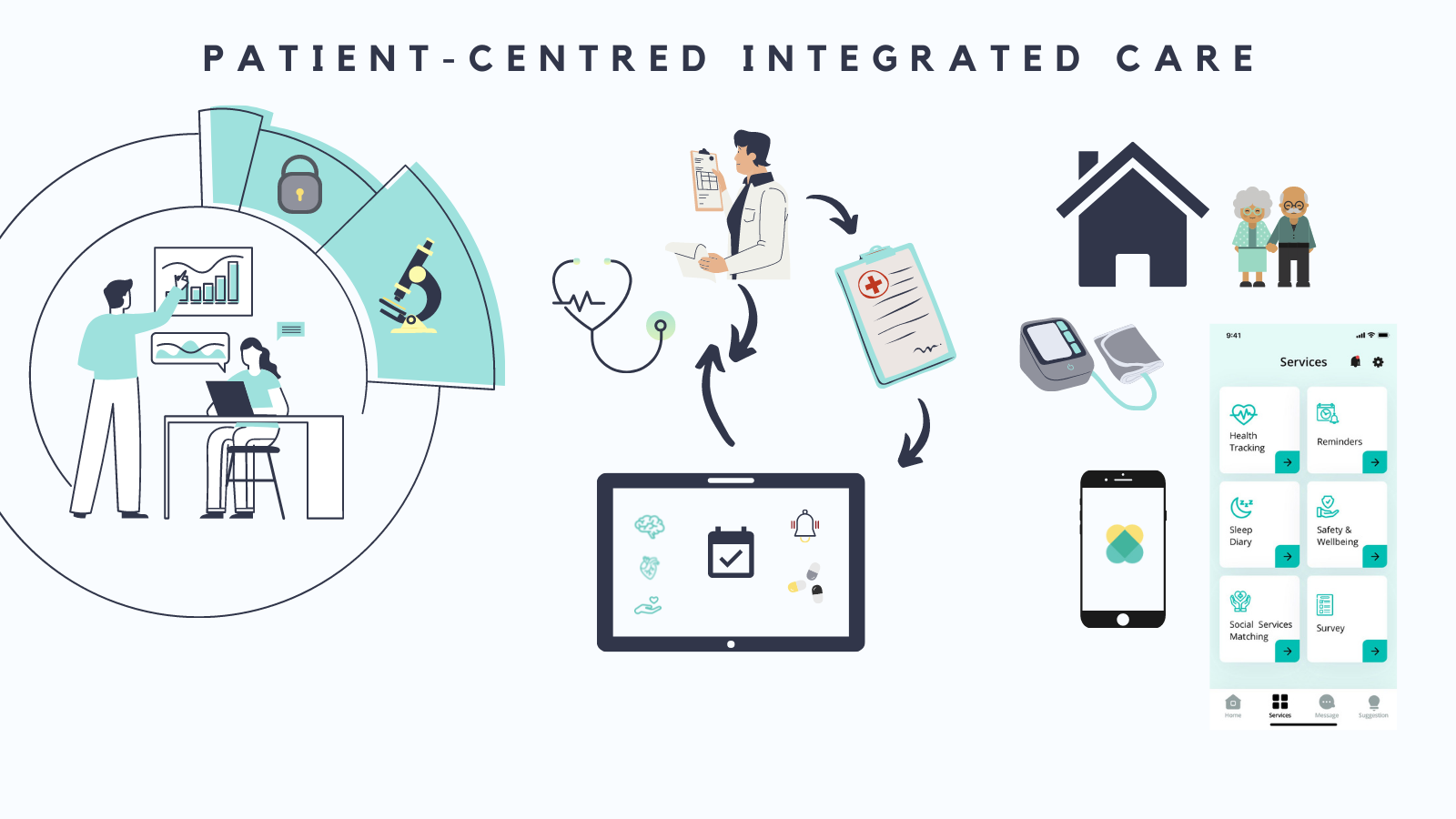

Said solutions are also targeted by the European project “TeNDER” (affecTive basEd iNtegrateD carE for betteR Quality of Life), which is currently running in the EU-funded Horizon 2020 programme. During the project, a technological, sensor-based system is being developed aiming to increase the autonomy of the user and thus also leading to an increased quality of life.

By giving the users possibilities to have control over their daily activities, TeNDER empowers them in various aspects. Therefore, users can manage their medication intake alone or schedule dates (medical or personal) with a Virtual Assistant and a Calendar-Function, which is especially important for users with memory impairment. Furthermore, users can track their activity with respective tools, or monitor their vital signs, like blood pressure or heart rate, and check their quality of sleep.

Moreover, with the linkage of various health sectors and services in the sense of integrated care, the TeNDER system connects patients with their respective physicians and carers. This way, more relevant information can be provided to make planned visits more efficient.

All in all, technology-based systems offer the user the means to lead a more independent and autonomous lifestyle despite the presence of disease, and empower him or her to take action in controlling their own health.

References

World Health Organization. (1986). The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index.html

World Health Organization. Division of Health Promotion, E., & Communication. (1998). Health promotion glossary. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Community research

Photo by NASA on Unsplash

First, we need to reinforce, raise awareness of and spread the well-established principles that govern what constitutes a valid intellectual contribution. Practices such as peer review, competitive process for funding research, requirements to publish data, and transparency about conflicts of interest are fundamental to academic life. Most people are unaware of these practices, which are the bedrocks of academic quality and progress […]

– Nemat Shafik, Times Higher Education (2017)

What’s in a fact?

Across the world, the terms ‘post-truth’ and ‘post-fact’ proliferate daily in connection to politics, science, and of course, COVID-19. If we are to believe the headlines, we live in a world where facts and expertise no longer shape realities, public discourse, or political decisions.

However, even as contradictory ‘facts’ circulate, all sides of recent debates assure us that they appeal to truth and fact. Each side accuses the other of being misinformed and spreading misinformation. These words are not misunderstood; indeed, a vague agreement of their meaning exists amongst all users.

Instead of implying that we’ve surpassed truth and fact, time and publication space may be better spent reminding us what it takes to build a fact. The methodologies may differ in each discipline, but a common principle runs through each process: the need for robust evidence.

For some, facts are observed and intuited, for others, they are supported by studies, experts, and institutions, and for many still, facts are the product of scientific consensus. However, as Nemat Shafik, Director of the London School of Economics, stated in 2017: it takes much more than one element to build a fact.

Communicating research

Good researchers are not only curious and knowledgeable, but they also take time to learn, innovate, and apply the methods that help frame each discipline, and they adhere to strict ethical standards.

Today, researchers are also tasked with communicating their work to ensure people’s trust in science. This is an important endeavour and it is a responsibility that extends beyond academia. It lies with politicians, news media, and primary education (to name a few).

As John Oliver points out, however, not all scientific studies out there are created equal. Some (often retracted for shoddy methodologies) seek to legitimise deplorable and potentially dangerous beliefs about race, vaccinations, gender, etc. Others are financed by industries for lobbying purposes. Still others are the product of unethical behaviour.

Algorithms may help weed out inaccuracies on social media, but this is a passive way of countering misinformation. The practice of communicating the basic tenets of good research empowers people and helps develop curiosity, as well as the skills to assess the strength of a fact.

Therefore, it is important to communicate not only what researchers do, but how they do it. How they build the robustness of a fact. Good science takes time, it’s founded on previous knowledge and uses different types of data, in many fields it must be reproducible, it should be peer-reviewed, it builds consensus, it accepts its limitations, and it is transparent about its methods and procedures.

We cannot be experts in everything, but understanding what makes “a valid intellectual contribution,” can help us discern between facts and information that disguises itself as fact.

The responsibility of projects like TeNDER

In TeNDER, user consent entails informed consent. Pilot participants will know exactly what types of tools will be used to assess their physical and mental health, how the data they generate will be processed, and how it will be protected.

Our user partners have passed rigorous ethical committee assessments and will be there to explain each tool and support all participants with the help of the technical partners.

The project consortium has also developed a model for co-creation with target users to ensure trust and that the tools are fit-for-purpose.

Like all Horizon 2020 projects, TeNDER is committed to the principles of open access. The consortium will widely disseminate results and submit periodical progress reports.

We will communicate throughout the project duration and hopefully beyond. As the preliminary pilots are set to launch soon with a cohort of people affected by Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, and Cardiovascular disease, we look forward to sharing this project journey with you.

To receive progress updates and other information please subscribe to our newsletter (scroll to the bottom of the page and enter your e-mail) and/or follow us on Twitter and LinkedIn.

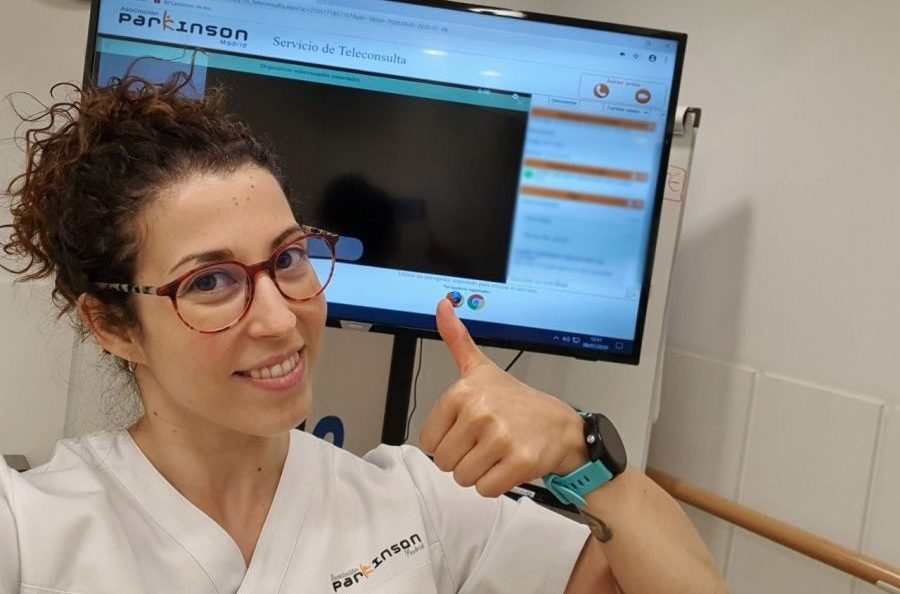

Adapting to a new reality: The experience of Asociación Parkinson Madrid

There is no doubt that the global pandemic caused by COVID-19 has impacted all sectors of society and the population as a whole. In this article, we will focus on the impact that it has had (and continues to have) on people affected by Parkinson’s disease and share the strategies Asociación Parkinson Madrid developed during the lockdown in order to alleviate this situation.

Parkinson’s disease is neurodegenerative and chronic. Today, there is no cure, therefore, treatment seeks to counteract symptoms with both medication and therapies with the aim of keeping the person autonomous for as long as possible and improving their quality of life. Both treatments, pharmacological and therapeutic, are essential for people with Parkinson’s.

The general lockdown that countries in Europe experienced led entities, such as Asociación Parkinson Madrid (APM), to implement telework solutions and teletherapies so that people affected by the disease could continue their treatment.

On 11 March, APM had to close its doors due to the deteriorating situation. At that time there were more than 600 patients following their rehabilitation at our centres and with home assistance. All APM professionals were teleworking by the end of March. We called patients to learn more about their needs and concerns, and to evaluate the impact COVID-19 and the lockdown measures were having on them.

Professionals were concerned about their patients’ therapies because it is known that long periods of inactivity can worsen symptoms. So, it was important that, given the impossibility of providing therapies at home and in APM centres, those affected by Parkinson’s disease could continue their therapies at home.

In this context, APM started providing physiotherapy, speech therapy, and psychological care, using new technologies, allowing us to maintain contact with patients. Although everything changed very quickly, APM’s response unfolded in stages.

At first, APM used social networks such as Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook to share exercise infographics. This enabled patients to follow therapeutic instructions. However, the lack of personal contact sometimes made it difficult to follow the steps laid out in the infographics. Sometimes patients phoned the association to request further explanations, sharing their difficulties in carrying out some of the exercises. Dealing with this aspect over the phone was very difficult for APM therapists.

The next step involved streaming the therapy sessions. The videos with the exercises performed by the therapist were previously recorded. Space and the home conditions were taken into account. The interaction in the YouTube chat was very positive, both between the patients and with the therapists, an aspect that was useful in improving the sessions.

The last step was to develop one-on-one tele-rehabilitation, which allowed patients to choose different rehabilitation sessions and have direct contact with their therapists.

APM therapists Jessica Jiménez Cruz and Rocío Martín Picazo, who were involved in this entire process, shared their experiences, pointing out the most positive aspects and the aspects that need to be improved.

Among the aspects that need to be improved, they both point out that there is still a technological gap in regard to older people’s digital skills. Older patients often turned to their relatives, grandchildren, and caregivers to overcome this difficulty and many learned from them. The gap remains, however.

From the technical point of view there was also an internal learning process, the first videos are of less quality compared to later ones where lighting or positioning were considered. Another issue that arose concerned the lack of interoperability between some of the devices, software, and video formats.

One of the positive aspects of tele-rehabilitation that Jessica Jiménez pointed out, has been that it allows therapists to personalise the sessions; that is, it allows people affected by Parkinson’s disease and their families to use this tele-space with their therapist to fit their specific needs. In addition, this experience has provided a new working model for professionals who until now were not usually considered for telework.

For Asociación Parkinson Madrid, there is no doubt that new technologies are the future and that more and more will be introduced in the field of health. Our next steps will include improving tele-rehabilitation and making it more accessible for a greater number of older people by helping them bridge the technological gap and adapt to a new reality.